‘The Greeks of Azov Region’ debuts in Chicago as Ukraine’s Greek diaspora is on the brink of extinction

Mariupol now lies mostly in ruins. A documentary premiering at UChicago shows the city’s last moments of freedom.

By Anna Savchenko

‘The Greeks of Azov Region’ debuts in Chicago as Ukraine’s Greek diaspora is on the brink of extinction

Mariupol now lies mostly in ruins. A documentary premiering at UChicago shows the city’s last moments of freedom.

By Anna SavchenkoWhen Anton Savidi produced a documentary in the summer of 2021 about the ethnic Greek villages scattered around Mariupol in southeastern Ukraine, he didn’t know he memorialized what may be the last traces of their diaspora ahead of the Russian invasion.

Savidi said the traditions and local Greek dialects the film crew captured are now in danger of becoming extinct.

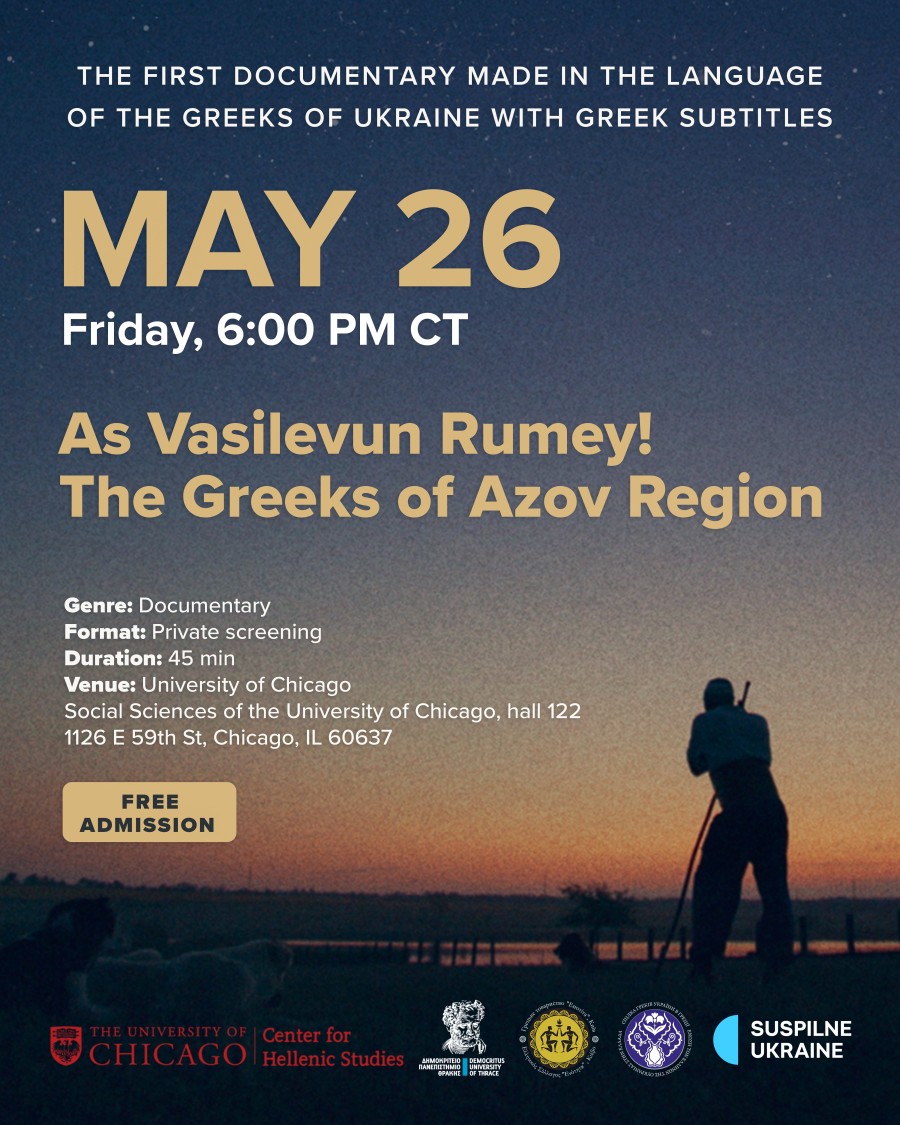

The documentary, As Vasilevun Rumey! The Greeks of Azov Region, premiered in Kyiv this April and will make its American debut Friday at the University of Chicago. The film meditates on nostalgia for pre-war Ukraine while also celebrating the simple life the Greeks of Mariupol lived, such as scenes of women cooking traditional dishes ahead of a wedding feast and men shearing sheep in open fields.

Savidi wants attendees to know the Donetsk region was once home to about 77,000 ethnic Greeks, making them the third-largest ethnic group after Ukrainians and Russians before the war uprooted their community.

All but three of their 48 villages are now occupied by Russian troops. The city of Mariupol — the capital of Ukraine’s Greek diaspora — lies mostly in ruins. And with no official death toll, Savidi can only speculate how many ethnic Greeks may have been killed by Russian shelling or how many ended up in Russia as part of Moscow’s evacuation efforts.

“A lot of people fled,” Savidi said. “A lot of people stayed. Some died.”

But life was different before the war. In one scene, several children stand on the stage of a rural theater exchanging lines of a play in Rumeika — one of the several dialects spoken by Mariupol Greeks. To the ear, it sounds like Greek interspersed with Ukrainian and Turkic words borrowed from the indigenous people of Crimea. It’s a language understood by only several thousand individuals today, Savidi said.

The recital is an exercise for the children to walk away with some knowledge of their forefather’s tongue and how it was lost over centuries of forced displacement under Russian rule.

The earliest Greek settlements on the coast of the Black Sea date back to at least 700 B.C. But the Greeks were displaced from their homes in Crimea in the 18th century by Catherine the Great. As a result, they founded the city of Mariupol on the northern coast of the Azov Sea. They named it the City of Holy Mary.

Then came the “Greek operation” of the Stalinist era in the late 1930s, which purged the community’s intellectual elite and forced others into silence about their heritage and ethnicity.

Cultural expression flourished in the post-Soviet vacuum, with community leaders making strong efforts to revive local dialects and traditions.

Now, Russian forces have decimated the cultural hubs that made Mariupol the stronghold of Ukraine’s Greek diaspora since the fall of the Soviet Union and with them, the documented archives of their plight.

“It’s like genocide for us,” said Svitlana Petropoulou, 35, a member of the Greek society “Enotita” in Ukraine, which helped produce the film and bring it to a Chicago audience.

The question of whether Ukraine’s Greek diaspora will survive the war is one that weighs heavily on Petropoulou and her family. Her great-grandfather was shot dead at the height of the so-called “Greek operation.”

“He was repressed just because he was Greek,” Petropoulou said. “He was proud of his origins.”

Petropoulou, whose family was displaced in 2014 after pro-Russian rebels seized her native city in the Donetsk region, carries this pride.

She wants to show Chicagoans “who have no idea who we are, what the difference is between Greeks in America and Greeks in Ukraine.”

For the Ukrainian Greeks alive today, it’s a matter of survival.

“Our historical roots run deep,” Petropoulou said. “If we lose this connection, who will we be?”

As Vasilevun Rumey! The Greeks of Azov Region will be shown in the language of Mariupol Greeks with Greek subtitles at 6 p.m. on May 26 in the social sciences building of the University of Chicago, hall 122, at 1126 E. 59th St., Chicago, Ill., 60637. Admission is free.

Anna Savchenko is a reporter for WBEZ. You can reach her at asavchenko@wbez.org.