This Procedure Can Spike Lead Levels In Your Water — But You Probably Wouldn’t Know About It

By Monica Eng

This Procedure Can Spike Lead Levels In Your Water — But You Probably Wouldn’t Know About It

By Monica EngWhen Chicago workers were replacing the water main outside Miguel Del Toral’s home, he said they accidentally broke the lead pipe that brought water to his building. As an acclaimed water scientist, Del Toral knew this mistake could cause spikes of toxic lead in his water for more than a year.

But when he actually tested his water, he said the results were especially “horrific.”

Del Toral was on vacation during that summer of 2012, so he had time to watch the workers as they repaired the lead pipe — called a service line — outside his Southwest Side home. He even took pictures as crews removed the damaged portion of the lead pipe and replaced it with a copper pipe.

This particular repair is discouraged by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Science Advisory Board and American Water Works Association. But it’s a standard procedure in Chicago when crews damage lead pipes during water main work, according to the city’s water commissioner, Randy Conner.

When Del Toral saw it happen, he knew to be cautious. So when the water was turned back on, he ran his faucets at full blast and collected all the sediment that came out. Then, he had it analyzed.

“I knew it would be bad, but what I found was scary,” he said.

Del Toral said the total sediment he collected during that long flushing period was “upwards of 400 milligrams” — about one hundred million times more than the level allowed in bottled water, which is routinely monitored for lead.

“It’s a dangerous amount of lead, essentially like a [bullet] slug,” he said.

As a scientist, Del Toral knew enough to check, flush and filter his water for more than a year after the pipe replacement. He said he also told the city about the high levels he found and warned three neighbors whose service lines were also damaged and partially replaced the same way.

But other Chicagoans in the same boat get no such warning. That’s because the city’s Department of Water Management does not notify residents when crews replace a damaged lead pipe with a piece of copper, a procedure that studies show can spike lead in home water for days, weeks, months, or even more than a year.

Instead, the department leaves flyers telling all area residents to run their water for at least five minutes when their service lines are reconnected. But the water department gives no additional notice to residents whose lead pipes were partially repaired with copper. After that procedure, the American Water Works Association recommends flushing all taps for at least 30 minutes.

Still, Chicago water officials aren’t breaking any laws.

Water department spokeswoman Megan Vidis wrote in an email: “We are in compliance with all federal, state and local laws in regard to any service line reconnections performed after we replace a water main and reconnect a customer to the new main to ensure the home has water service restored.”

It’s true the city is not violating the U.S. Lead & Copper Rule, which regulates municipal water systems and doesn’t require notification after partial replacements are done as part of a repair. But water experts like former Environmental Protection Agency scientist Elin Betanzo notes the federal law was created in 1991, long before most research on the dangers of partial replacement came out.

Further, an EPA Science Advisory Board concluded that partial replacements done as repairs, as they are in Chicago, may be even more dangerous than those that do require notification because follow-up tests aren’t required.

“There is nothing that stops [cities] from telling residents,” Betanzo said. “The regulation is the floor, and they can do anything more they want to protect public health.”

But it’s not just scientists who are concerned about the dangers of this procedure. Both of the city’s mayoral candidates have come out strongly against the practice.

Last fall, Toni Preckwinkle said if elected she’d “stop harmful ‘partial’ replacement of service lines.” In the meantime, she wants residents to be notified so they can “take the necessary precautions, and the Department of Water Management should distribute information educating homeowners on what precautions should be taken.”

Lori Lightfoot agrees and says the city needs a plan that focuses on “full line replacement and limits partial service line replacement as much as possible to avoid harmful spikes in lead levels.” She also favors “proactive notification of impacted households.”

How many Chicago homes could be affected?

Water officials won’t say how many times this procedure has been done since Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s signature water main replacement project began more than seven years ago.

After multiple requests, department officials agreed to turn over just one month of potentially incomplete records, showing at least nine copper replacements performed in September 2016. The project has been going for 87 months and is more than two-thirds done, but the total number of affected homes remains unknown.

What we do know is city workers have replaced more than 700 miles of water mains connected to hundreds of thousands of homes. And about 80 percent of those homes are hooked up to the water main through lead service lines that are the primary source of lead in drinking water.

That’s because water is generally lead-free when it leaves the filtration plant and rolls through the iron water mains. But when it travels into homes through lead lines, it can pick up lead, especially when the line is jostled or the water has been sitting in the pipes for several hours.

Health authorities stress there is no safe level of lead exposure. In adults, lead can aggravate heart disease, while in children and pregnant women, the toxin can damage a child’s brain development. One 2015 study of Chicago children — who have some of the highest blood lead levels in the nation — showed that kids with even low levels of lead in their blood were 32 percent more likely to fail standardized tests by third grade.

Del Toral, a government scientist who spoke to WBEZ only as a concerned Chicago resident, eventually moved to a newer home with a copper water service lines so he wouldn’t have to worry about lead in his water.

But about 360,000 Chicago homes still have lead service lines. These pipes can leach lead into water even when undisturbed. But that risk grows when those pipes are jostled, cut and joined with another metal like copper.

What are partial lead service line replacements and why are they so dangerous?

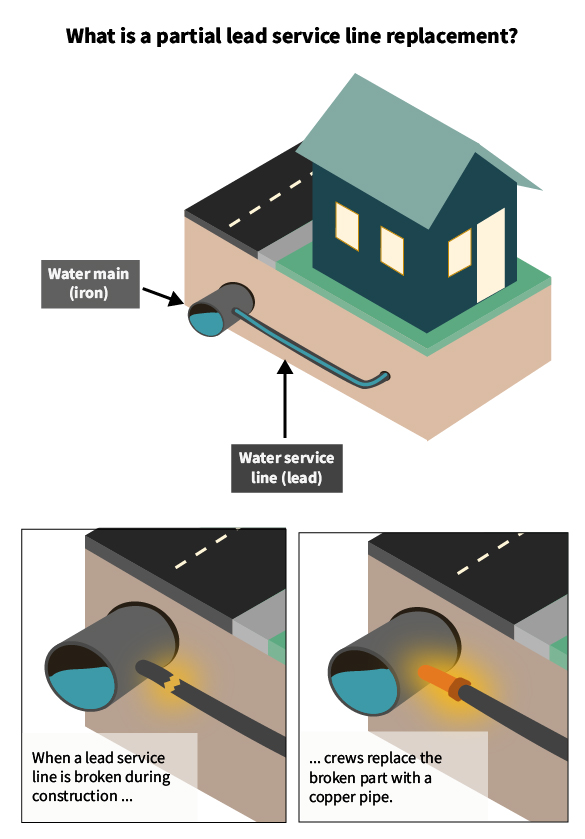

A partial lead service line replacement usually involves replacing a part of the lead service line that is closest to the water main with another material. That portion is usually owned by the municipality until it reaches the homeowner’s property line.

Vidis, the city water department spokeswoman, insists that a repair is not considered a partial lead service replacement unless the copper pipe runs fully “between the water main and the buffalo box [near the property line].”

But water experts, including Betanzo and Del Toral, generally consider any partial replacement of the lead service line a partial lead service line replacement. They further noted the detrimental effects are similar regardless of the specific length of the copper replacement piece.

Conner, the water commissioner, even agreed that the repairs his crews do on broken lead service lines constitute a de facto partial lead service line replacement.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the dangers of partial lead service line replacements. Many were summarized in a 2011 EPA Science Advisory Board report. But more recent analyses, including a study by researchers in Montreal, continue to bolster the conclusions that the procedure often causes short- and long-term lead elevations in water, including erratic spikes for up to 18 months.

Betanzo said these high levels are because of three factors.

Jarring and banging on the pipe during main replacement, which can dislodge pieces of lead and sediment inside the pipe.

Cutting the pipe, which can break off a protective coating that helps keep lead from leaching into the water.

Joining dissimilar metals like lead and copper, which can cause galvanic corrosion that introduces more lead into the water. This reaction can continue to cause lead spikes for a year and a half after the work is done.

“I frequently call partial lead service line replacement a really expensive way to increase the risk of lead exposure in a home,” Betanzo said. “There are all of these well-documented risks of increased lead exposure from this. And if nobody is telling the homeowner … they are just drinking it and getting exposed and suffering the health effects without any opportunity to take protective measures.”

Mae Wu, an attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council who works on lead issues nationally, was aghast to hear that Chicago continues to do partial replacements without alerting residents.

“Oh my goodness, that’s terrible,” she said. “At the very minimum they should be telling residents when partial replacements are happening so they can protect themselves.”

That protection, she said, can include prolonged flushing and filtering, but preferably replacement of their entire lead service line while the streets are torn up for the water main work. This is something the NRDC and others have been pushing municipalities to offer homeowners nationwide.

Dozens of communities now offer this service and financial help. But Chicago officials offer no such options, and insist that homeowners who opt for full replacement must foot the entire bill, which can be upwards of $5,000.

What Chicago and other cities do about lead in the water

For years, the Emanuel administration has insisted that Chicago does not have a problem with lead in the water. But last fall, the Department of Water Management announced a feasibility study on finally replacing the city’s 360,000 lead service lines that were required by the city until 1986.

The water department said the study will not be finished until late spring — after Emanuel has left office.

In the meantime, the most extensive advice the city offers citizens is to regularly flush their water. “It’s particularly important to flush your system for 5 minutes after it has been stagnant for six hours or more to maintain water quality,” according to the water department’s website. This is despite frequent reminders from the department to conserve water.

For most residents, following the city’s advice would mean flushing for at least 10 minutes a day. So just how much water would be used if all residents with lead lines read and practiced this daily advice? WBEZ measured it at a home kitchen sink and found the following.

5 minute flush = 7.5 gallons

Twice a day = 15 gallons

15 gallons x 360,000 Chicago homes = 5.4 million gallons per day

That’s 5,400 “gallon units” — and the city charges homeowners $7.90 per gallon unit.

5,400 gallon units x $7.90 = $42,660 per day

$42,660 x 365 days = $15.6 million

In contrast, dozens of other municipalities across the nation and even Illinois are moving to deal with their lead problem permanently. They’ve started — and some have even finished — full lead service line replacement programs by offering partial or total funding help to homeowners.

In suburban Elgin, homeowners will now be required to take out their full lead service line — with financial help from city government — whenever any ground construction work is done in their area. If residents don’t replace their lines, they must commit to drinking bottled water for two years.

And officials in downstate Galesburg plan to remove and replace half of the city’s lead service lines by the end of the year using substantial government grants.

Last year, the state of Michigan passed a law that requires all municipalities to come up with full replacement plans, and bans partial lead service line replacements in all but emergency situations.

In Philadelphia, the city offers free lead service line replacement to residents when crews do water main on their street, whether crews break anything or not.

Meanwhile in Chicago, the city with one of the largest concentrations of lead service lines in the country, officials haven’t even agreed to craft a plan for removal.

Another lead problem against the backdrop of many

Revelations about these undisclosed dangerous procedures arrive against the backdrop of several other ongoing lead controversies in Chicago.

- Water main work making things worse: An EPA analysis showed the city’s ongoing water main replacement work has been raising lead levels in nearby homes by disturbing protective coating in the lead service lines.

- Tests show high lead in home water: A Chicago Tribune analysis of voluntary home water tests last year showed that 70 percent of Chicago homes tested had some lead in their water. About one third had more lead than the 5 parts per billion that is allowed in bottled water.

- Water meters associated with high lead: Last fall, the water department released the first batch of results in its study of homes that have installed water meters. So far, officials said, nearly a fifth of homes tested have been found with three times more lead in their water than would be allowed in bottled water. The department said it still doesn’t understand why. But in the meantime, the city is offering water filters to residents who have joined the city’s Meter Save program.

- Schools and park water fountains contaminated: Over the last few years, tests have detected lead in hundreds of park and school water fountains, causing officials to slowly replace them, keep them running non-stop or turn them off permanently.

What’s next under the new mayor?

Although Emanuel has been slow to address these daunting and expensive problems, the two final candidates for mayor have promised bolder action on partial replacements and Chicago’s broader lead problem.

Preckwinkle has promised to improve water testing, create a lead line replacement schedule, bundle those replacements for cost efficiency and prioritize giving repair work to African-American and Latino firms. She said she also favors finding government funds to help homeowners, especially low-income residents, pay for the full replacement.

Lightfoot has criticized the Emanuel administration’s practice of testing just 50 homes every three years, the minimum required for federal lead compliance. She said she would expand lead testing, add full lead line replacements to city construction projects, offer financial help for full lead line removal and provide residents with filtration systems in the meantime.

Ald. George Cardenas, 12th Ward, and others have been pushing for City Council hearings on lead in for nearly a year, only to be thwarted by Emanuel’s City Hall supporters. He said the words from the two mayoral candidates make him hopeful.

“I am looking forward to finally having the debates we should have been having all along on lead,” he said. “I am looking forward to a new administration that is pro-environment. I just hope their rhetoric matches their actions after the election.”

Addressing these problems and eventually removing all lead lines from the city would require considerable time and resources to fix. But simply alerting residents about this risky procedure could be the first step in catching up to other cities.

Correction: A previous version of this story misidentified a lead pipe in an image. The caption has been updated.

Monica Eng is a reporter for WBEZ. You can follow her @monicaeng.