The Fight To Preserve The Legacy Of Nancy Green, The Chicago Woman Who Played The Original ‘Aunt Jemima’

By Katherine Nagasawa

The Fight To Preserve The Legacy Of Nancy Green, The Chicago Woman Who Played The Original ‘Aunt Jemima’

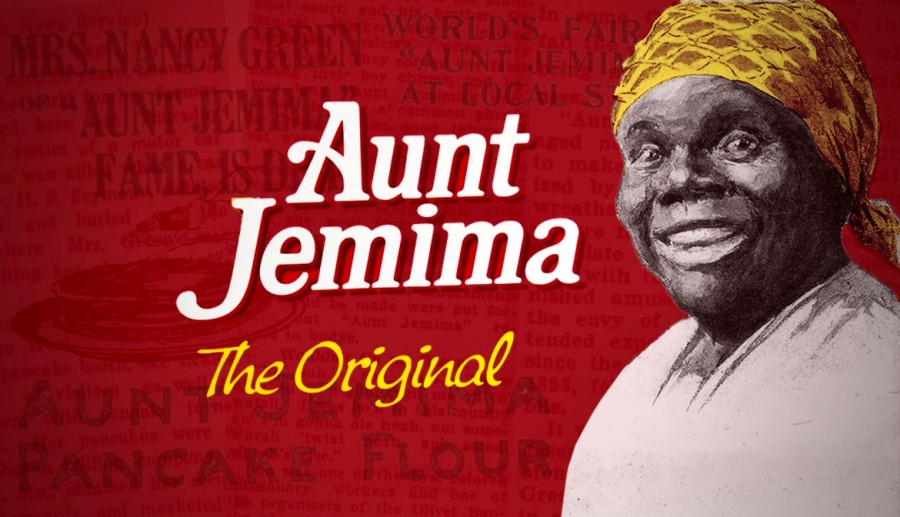

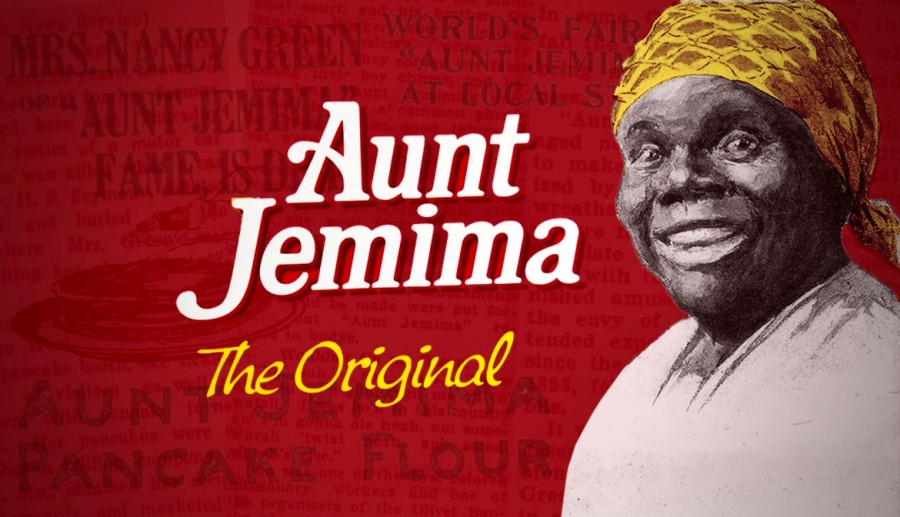

By Katherine NagasawaYou probably don’t know the name Nancy Green, but you’d recognize her face. The Chicago woman originally portrayed the Aunt Jemima trademark, and efforts are being made to preserve her legacy as Quaker Oats removes the Aunt Jemima name and image from their popular pancake products.

The brand name Aunt Jemima — which Quaker Oats officials admitted this week is “based on a racial stereotype” — was derived from an African American “mammy” character from a popular minstrel show in the late 19th century.

Green, a former slave who moved to Chicago to work as a caretaker for a prominent white family, was hired to portray a living version of the character at the 1893 World’s Fair, according to her obituaries. She was later hired to play the role for the pancake company until her death.

Although the name Aunt Jemima is well-known, Green’s is not. And one Chicago historian worries that removing the Aunt Jemima image could erase Green’s legacy — and the legacies of many Black women who worked as caretakers and cooks for both white families and their own.

“Black mothers are not irrelevant,” said Bronzeville Historical Society President Sherry Williams. “I look at Nancy Green as a Black mother figure, and Black women are the lifelines for generations, both Black and white.”

Through extensive research, Williams learned Green was a philanthropist and ministry leader. Williams is now attempting to place a headstone on Green’s unmarked grave, to help preserve the memory of the real woman as the character she portrayed fades away.

Discovering Nancy Green

Williams said she grew up seeing the Aunt Jemima trademark in many of its iterations, but she didn’t learn about Green until she started working as a community historian in the Bronzeville area.

Williams said she became fascinated with Green and pored over newspapers to find clues about Green’s life in Chicago. According to a 1923 obituary in the Chicago Defender, Green was born into slavery in Montgomery County, Ky., in 1834 and moved to Chicago to serve as a nurse and caretaker for the prominent Walker family.

Several obituaries, including one Williams found in the Sunday Morning Star, claim it was Green who originally came up with the pancake recipe that would go on to be sold as the Aunt Jemima mix. According to the obit, Green made pancakes for the Walker brothers, who then spread the word of Green’s legendary pancakes among their friends. Eventually, word reached executives at the Aunt Jemima Manufacturing Company, who ultimately hired Green to make pancakes and portray Aunt Jemima at the 1893 World’s Fair.

After the fair, Green was offered a lifetime contract with the pancake company and traveled the country on promotional tours until she died at the age of 89 after being hit by a car while walking on 46th Street.

Although Aunt Jemima became a household name for the next century, very little was documented about Green’s life and work in her community.

“With media being so totally controlled by white management, those stories about Black lives would have only been in publications like the Chicago Defender,” Williams said. “Outside of that, there are not many news sources that would have contributed greatly to the narrative of her life and her work.”

Through the Defender obituary, Williams said she learned Green was a philanthropist and ministry leader. She was one of the founding members of Olivet Baptist Church, the oldest active Black Baptist church in Chicago.

Romi Crawford, who researches African American visual imagery at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, said Green had social and economic mobility not many African American women had at the time, which she leveraged to further the work of her church.

“That is absolutely the irony, that she is playing a role: a derogatory type and caricature of Black women,” she said. “In actuality, this is a Black woman who was moving around the country and, in a way, the world. … Her actual mobility in so many ways defied the stasis of the problematic caricature-type.”

Finding Nancy Green’s grave

After learning more about Green’s life, Williams said she became determined to find Green’s grave and honor her with a headstone.

“In Black communities, we visit our grave sites. We have picnics at grave sites. We have a tradition called grave ‘Decoration Day,’ ” Williams said. “Out of the countless notables in Chicago’s cemeteries I’d like to have a headstone placed on … the No. 1 person I want to put a marker down for is Nancy Green.”

Using Green’s death date, Williams said she worked with Oak Woods Cemetery staff to locate the plot of land where Green was buried with no marker in 1923.

But Williams still wasn’t able to get Green a headstone.

The cemetery has a policy that the grave plot property owner — or a living descendant — has to give permission for any gravestone or marker. But finding a living descendant of Green is no easy task. At the time of Green’s death, she had already lost her children and husband, and was living with her great nephew and his wife, Williams said.

It was this great nephew, Luroy Hayes, who was listed in records as the person who arranged Green’s burial in Oak Woods cemetery.

Williams said she used ancestry.com, along with the “good old White Pages,” to try and track down multiple generations of Luroy Hayes’ family.

She said she also reached out to Quaker Oats about whether they would support her in getting a monument for Green’s grave.

“Their corporate response was that Nancy Green and Aunt Jemima aren’t the same — that Aunt Jemima is a fictitious character,” Williams said.

So Williams had to go at it alone. Last year, she finally connected with an elder in the Hayes family who put her in touch with Marcus Hayes, Green’s great-great-great-nephew.

Hayes, who lives in Huntsville, Ala., told WBEZ his father died when he was a toddler, so he and his brothers never knew much about the paternal side of their family.

“We’ve all wondered about our ancestors and wanted to know where we came from,” he said. “It means the world to me. It actually inspires me to even do more to make sure I’m leaving a legacy for my children as well.”

Remembering Nancy Green, as Aunt Jemima fades away

After nearly a decade of effort, Williams said she finally received approval for a headstone for Nancy Green in March. A woman who answered the phone at the cemetery Friday morning confirmed the policy requiring a living descendant to approve a headstone and directed questions about why the process took so long to a spokeswoman, who was not immediately available for comment.

Williams said she’s currently raising the funds to order the headstone and hopes to fly Marcus Hayes and other living descendants to Chicago for a memorial ceremony this fall, if the pandemic subsides.

“I do understand the sensitivity of the name and the brand,” Hayes said of Quaker Oats’ decision. “But at the same time, I don’t want Nancy Green’s legacy and what she did under that name to be lost.”

Williams agrees that getting rid of the Aunt Jemima logo obscures Green’s legacy, which is why she believes it’s more important now than ever that Green have a permanent headstone in Chicago.

“It would certainly represent acknowledging the fact that she is real — Nancy Green is a real human being who worked as a living trademark for a product that made millions,” she said. “I think that would raise the visibility of that by placing the headstone and having a meaningful remembrance gathering.”

Crawford, the researcher at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, said she hopes Green is remembered for more than just playing a racist stereotype.

“The problem with the portrayal is that she was, and Black women subsequently are, plagued by representations that don’t align with the scope of their ambition, desires and abilities,” she said. “Knowing her story will help debunk the caricature.”

Williams said beyond the caricature, Green’s portrayal of Aunt Jemima reminds her of other powerful, Black women in her family, who she believes should be celebrated.

“My mother and grandmother cooked and cleaned in white homes,” she said. “My grandmother received little money for her labor, and then she had to turn around from those households and come back to her own house and take care of her own aging mother and young children.”

Williams said she wishes Quaker Oats would invest more money into preserving the legacy of women like Green and Black women caretakers, rather than erase the logo altogether.

“Instead of spending the money on new packaging, put some narrative about the role of Black women in taking care and feeding this nation from enslavement to now,” she said. “And educate [consumers] about Nancy Green herself, whose likeness was used for this package.”

She said these women were exceptional in their contributions to both Black and white society.

“There’s no other segment in society who did everything to take care of everybody,” she said. “That has always been the Black woman.”

Katherine Nagasawa is WBEZ’s audience engagement producer. Follow her @Kat_Nagasawa.