CPS Remote Learning Begins Monday. What That Looks Like Depends On Where You Live.

When class resumes, it’ll vary greatly from school to school. Some will be mostly paper packets while others will be mostly online.

By Sarah Karp

CPS Remote Learning Begins Monday. What That Looks Like Depends On Where You Live.

When class resumes, it’ll vary greatly from school to school. Some will be mostly paper packets while others will be mostly online.

By Sarah KarpUpdated April 8, 10:20 a.m.

When Chicago public schools formally begin remote learning next week after shutting down nearly a month ago, Lee Elementary School principal Lisa Epstein is expecting her teachers to pick up where they left off.

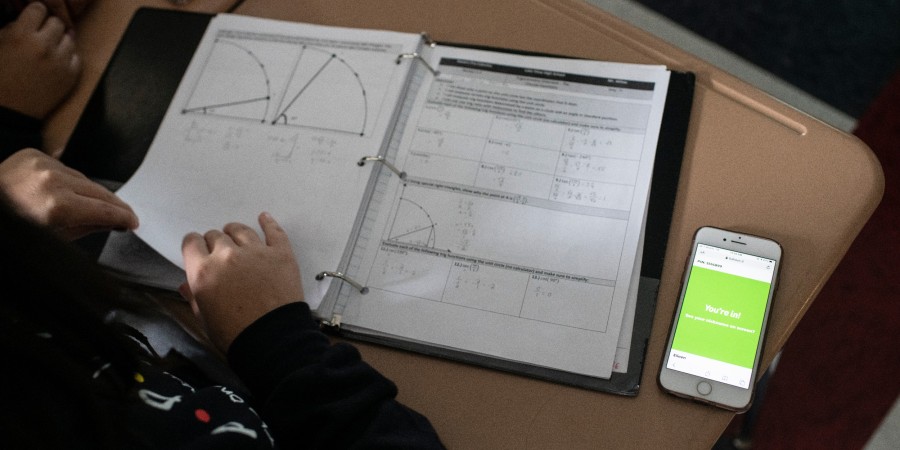

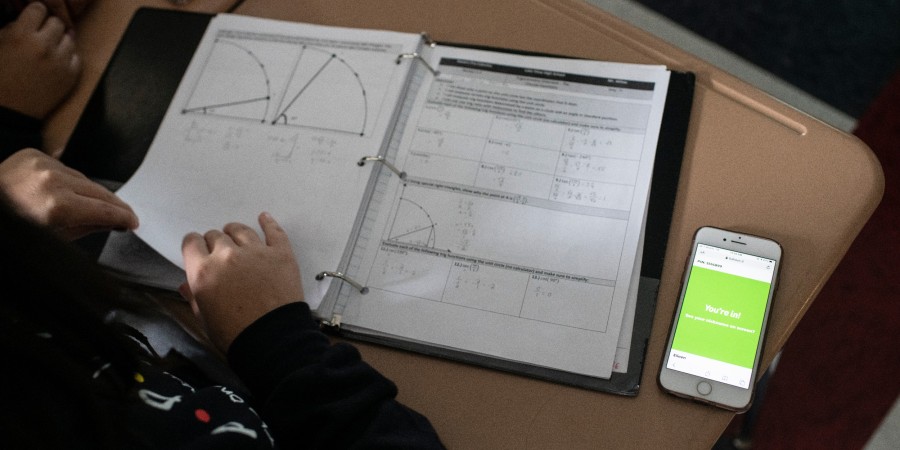

Unlike other schools that have few computers and limited ability to use them, Lee Elementary in West Lawn on the Southwest Side has a computer for every student and they are adept at using them.

“I honestly believe that when our students are able to see their teachers face-to-face on technology that they are going to be excited to know that they can continue to learn,” she said. CPS students just finished up two weeks of enrichment and extra credit work with limited interactions with their teachers.

When remote learning starts on Monday, it will look very different from school to school. While Lee will be almost entirely online, teachers at other schools may post lessons online but know many of their families will pick up paper assignment packets and then reach out to their teachers if they need help.

Chicago Public Schools leaders point to the digital divide as a key reason why moving classes entirely online is impossible. To attempt to close that, it is in the midst of trying to get 65,000 computers and laptops moved from schools to student homes. Additionally, in the coming weeks, it will distribute 37,000 new computers to fill in the gaps.

But even with this, school district officials acknowledge that some schools will transition to online learning much more easily than others. That’s because there is wide variety between schools — both in how much hardware they have and in their student and teacher computer literacy skills.

No comprehensive tech plan for years

This is an outgrowth of Chicago Public Schools lacking a comprehensive technology plan. For years, there has been no plan spelling out how many computers each school should have and how they should be incorporated into the school day.

It was only last school year that the district adopted a five-year vision that includes a goal of a computer or laptop for every student. It pledged $125 million over four years to modernize technology.

So far, the school district says it has spent $57 million to bring one-to-one technology to 76 schools, with more being added by the end of the spring.

Historically, principals have driven the amount of technology in their schools and how it is used, said Elaine Allensworth, the director of the University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research.

The consortium stopped studying technology use in Chicago Public Schools in 2013, partly because there didn’t seem to be much interest. But Allensworth said she believes that little has changed since then.

Schools “really differed based on whether a principal thought it was important, whether there were the resources to keep technology updated and whether it was a priority in the school to make sure students were developing skills,” she said. “At some schools, students were getting a lot of familiarity at using technology, to interact with each other and interact with their teachers to complete assignments, and other schools not so much.”

Allensworth said these differences will be exacerbated as schools try to transfer learning online.

“The digital divide will show up strongly”

There are many reasons why principals may not have prioritized technology. These include directing scarce resources for other needs, wanting to focus on other areas, like the arts, or being opposed to excess technology in schools, especially in the younger grades.

Allensworth also notes that studies have shown online learning is not as effective as in-person interaction between students and teachers, especially for struggling students.

A counselor at a far South Side elementary school, said her school serves among the poorest students in the city and spends its budget on things like supporting homeless students and crisis intervention. The counselor didn’t want to be identified for fear of facing repercussions for talking openly about the challenges her school faces.

She said past principals have not emphasized incorporating technology, and the current principal is new this year. A big problem at her school, as well as others serving poor students, is high principal turnover. State data shows it has gotten a new principal every other year for the past six years.

Now, the counselor is worried about what the lack of technology use will mean as the school tries remote learning.

“I definitely know that the digital divide will show up strongly,” she said. “Just like you have students who don’t have technology knowledge and access, their parents — the ones who are at home with them — have some of the same deficits and then you have an instructor who has some of the same deficits.”

Seth Lavin, principal of Brentano Elementary in Logan Square, said he also is worried. He made a conscious decision not to make technology a big part of classes at his school.

“We are not a technology-obsessed school,” Lavin said. “We don’t use a lot of apps, we are not very online, we really prioritize face-to-face interaction, inquiry learning, project-based learning, human-to-human learning.”

Even before the school district directive to distribute computers, Lavin said he and his staff were reaching out to every student to see if they needed help getting online. He said they’ve already reached about 90 percent of the 600 students and delivered computers to about 60 of them.

He said he is still trying to assess what more is needed and if he has enough computers in his building.

But he said he is deeply troubled by the rush to online learning in the midst of a crisis in a country and city that has not prioritized making sure all children have access to the internet and the know-how to use it.

“Kids are scattered. Kids are cut off,” Lavin said. “Some kids are connected and some are not. It is unfair. It is inequitable. You cannot move forward right now without also leaving kids behind, and that’s awful.”

Sarah Karp covers education for WBEZ. Follow her on Twitter @WBEZeducation and @sskedreporter.

This story was updated to include new figures from Chicago Public Schools for spending on technology.